TRANSLATION

E X C A V A T I N G E A C H L A Y E R

why monologues?

The typical audition for stage actors lasts three minutes: 16 bars of a song, and a short monologue. Depending on the play, actors select either a contemporary monologue or a classical one—almost always from Shakespeare. Yet plays from antiquity are loaded with classical monologues too. The problem is they’re usually translated by, well, stodgy scholars with little regard for modern actors. Which is where Deme Creative Arts swoops in.

why him?

Demetra began translating classical monologues from ancient Greek drama in grad school. She selected monologues spoken by women, which led her to the tragedies written by Euripides. Of his 90+ plays, less than 20 survive, a tragedy in itself. Euripides wrote from the female perspective, an approach not exactly embraced by other ancient playwrights—another tragedy in itself. He portrayed powerhouse characters: Hecuba, Clytemnestra, Phaedra, Medea. Their distrust, passion, and rage are palpable, regardless the style used to translate their monologues.

why not literal?

Scholars adhere to a strict translation of ancient drama. This style is arguably more accurate, yet inarguably less accessible. The legendary Octavio Paz described literal translation as “a string of words” and “a glossary rather than a translation.” See, this word-for-word breakdown of a source text just doesn’t speak to modern audiences. Instead—and somehow—the grammar and syntax of the original work must be both translated and transformed.

why literary?

Literary translation, alternatively, captures the intent and feeling of the original text. It stays “loyal to the spirit, not the letter,” as the lyrical Willis Barnstone explained. This literary style infuses the aesthetics of creative writing into a character’s dialogue, all while remaining devoted to the truth and emotion of each scene. Despite our best attempts, any translation is riddled with awkward phrases, unfamiliar expressions, and doubt.

Take, for example, an expression that occurs in many of Euripides’s plays: “to tug at your beard.” Weird, right? Within the historical context, however, we learn it is actually an affectionate gesture where kids lovingly grab their dad’s facial hair. Still weird? Not to anyone with toddlers.

Even monologues translated in a literary style require in-depth study and historical awareness on the actor’s part; they should read the entire play, identify their character’s objectives in each scene, and not only make sense of but believe in every line of dialogue, whether unfamiliar to them or not.

Let’s demo a translation of lines 1146–47 from the play Iphigenia in Aulis, spoken by Clytemnestra:

ancient Greek?

“ἄκουε δή νυν: ἀνακαλύψω γὰρ λόγους,

κοὐκέτι παρῳδοῖς χρησόμεσθ᾽ αἰνίγμασιν.”

literal?

“Listen binding now: I uncover speech,

no longer will I proclaim hinting obscurely.”

literary?

“Now listen. I will speak plainly.

No more hints or riddles.”

Here’s another translation of line 1392 from Iphigenia in Aulis, spoken by the title character:

ancient Greek?

“εἰ βεβούληται δὲ σῶμα τοὐμὸν Ἄρτεμις λαβεῖν,”

literal?

“wish / but / body / my / Artemis / receive”

literary?

“Artemis wishes to receive my body.”

Hold on. So in the play, Iphigenia learns that instead of marrying Achilles, she’s actually getting slaughtered at an altar dedicated to goddess Artemis so daddy can sail his ships to Troy. As a literary translator attempting to capture the spirit of both vengeful Artemis and young Iphigenia, “wishes to receive” sounds way too gentle. Let’s replace it with a more powerful verb:

“Artemis demands my body.”

Δ

will we relate?

Slaughter. Revenge. Sacrifice. These are dark themes. Whether translated literally or literarily, whether spoken by the most skilled and studious actor, will these classical monologues be comprehensible to a modern audience? How can we justify the actions of these ancient characters? How can we fathom their grief and suffering?

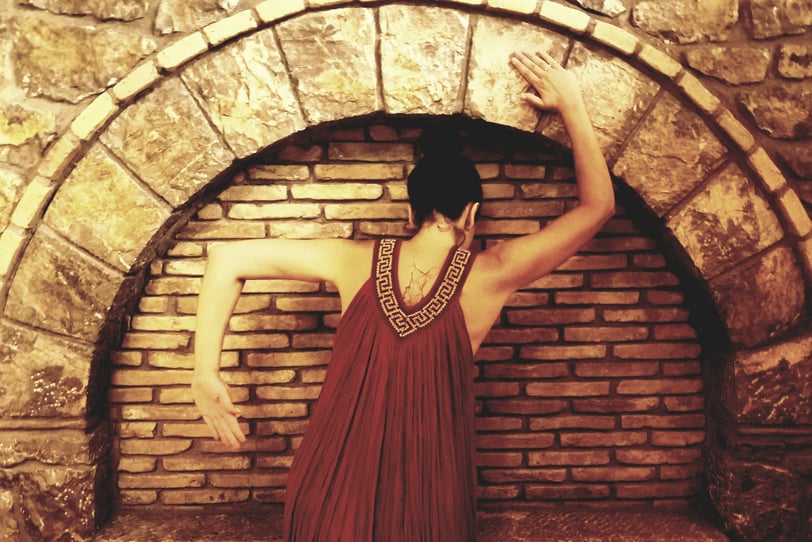

Deme Creative Arts wants to unearth these answers. In 2025, nearly 2,500 years after Euripides etched his tragedies onto papyrus, Demetra is seeking actors of any age and gender to perform her translated monologues. If this project speaks to you, then voice your desire.

let’s excavate antiquity

DEME CREATIVE ARTS

by Demetra Perros Rivard, a Greek American author, actor, and advocate who uses theatre to spread awareness about mental health

Contact

MEMOIR

demecreativearts@gmail.com

+14064311158

© 2012–2025.

Deme Creative Arts.

All rights reserved.

© Photo Credits: Meadowlark Images.

Sally Rappold. Magdalen Powers.

Litsa Productions International.